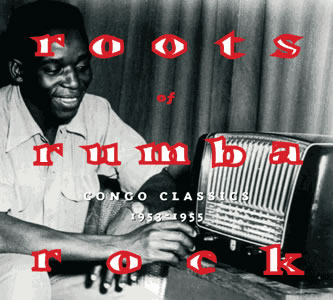

This essential collection documenting the early days of Congolese pop was finally re-issued in 2006, this time as a double CD including both of the separate, original volumes.

Lovingly put together by Congotronics man Vincent Kenis, RRR contains 40 delightful tracks and chronicles the birth of what was to become Africa's most popular musical style.

The origins of Congolese rumba, its strange links with traditional music, French crooners and Belgian brass bands... the spectacular reappropriation of Afro-Cuban music by Kinshasa musicians who recognized some of the old likembe (thumb piano) patterns originally brought to Cuba by deported Congolese slaves and proceeded to adapt them to the electric guitar... the social context, the lifestyle of Congolese musicians in the early Fifties... all of that and much more is extensively described in the liner notes written by Kenis and based on interviews with musicians from that era.

The artists featured include BOWANE, DE WAYON, LIENGO, ADIKWA, FRANCO (then in his early teens) and some other founding fathers of rumba.

In the early Fifties, Kinshasa (then called Léopoldville) became a musical beehive. Being the capital of a country the size of a continent, it was a meeting point for a wide variety of ethnic groups which soon merged their traditions to create new musical styles. But the main reason why the music of Kinshasa grew so strong and conquered all Africa lies in its spectacularly successful reappropriation of Afro-Cuban music, which was instantly recognized and adopted as a prodigal son coming back home. Which of course it really was: only two generations had passed since the end of the slave trade from Congo to Cuba, and most elements in Cuban music sounded very familiar to Congolese ears.

Despite its brutality, the Belgian colonial system didn't interfere much with the social life of the 'natives'. On the contrary, to attract cheap labor towards the industrial centres, the powerful Radio Congo Belge broadcast intensively its local music, not suspecting that it would be perceived all around Africa - just like rock'n'roll was perceived in Europe and the USA at the same moment - as something completely new, radical, exciting and subversive, because it suggested a modernity which owed nothing to the Europeans.